Rogue One is definitely my favorite of the Disney-era Star Wars products. I love it much more than the other four Disney-era movies, and as good as The Mandalorian is, I still think that Rogue One has the perfect blend of harsh action and traditional Original Trilogy Star Wars vibes.

And while I won’t go so far as to blaspheme the OT and say that Rogue One is my favorite, on any given day I would probably prefer to watch Rogue One to almost any other Star Wars movie or show.

(I am writing this the week before Andor is released on Disney+, because I want to get these thoughts out now, before they may be superseded by – or reinforced by – the new look at the early days of the Rebellion.

One thing that I love about Rogue One is how it portrays the Rebellion – gritty and rough, probably even lost in its ways, and certainly without direction. We see the Rebellion in a different light than the OT Rebellion, even though Rogue One occurs just hours or days before A New Hope.

The Rebellion we see in the OT portrayed as representing good. It appears to us as a moral force, representing the “good guys.” The contrast between the Rebellion and the Empire in the OT is stark – the Rebellion clearly stands for good, while the Empire stands for evil. We see the evil of the Empire in the first scene, as the Executor Star Destroyer runs down the Tantive IV. Even ignoring the visual and musical cues that tell us that the Empire are the “bad guys,” all we see of the Empire are evil acts: After killing a bunch of overmatched Rebels, Darth Vader saunters in and murders the Rebel officer with his own bare hands; we see the threatened (and presumed) torture of Princess Leia; and we see the destruction of Alderaan, both through Leia’s eyes and through Ben Kenobi’s sensing. Watching A New Hope more closely, we hear that the Emperor has taken the un-democratic step of dissolving the Senate; we see that the destruction of Alderaan was done solely to coerce Leia into divulging the location of the Rebel base; we see that Luke’s aunt and uncle, along with a few dozen Jawas, were killed in cold blood by Stormtroopers; and we see the Empire blockading and harassing the residents of Mos Eisley.

The Rebellion, on the other hand, is shown by its opposition to the evil of the Empire. We don’t see the Rebellion necessarily as good; what we see is a group of people standing in opposition to the evil of the Galactic Empire. Their morality is implied, but all we see are a group of people being hunted by the Empire.

Probably the only ambiguity displayed by the Rebellion, the only glimpse into its amorality, is when Leah tried to use the cover of being on a “diplomatic ship” to cover what is an act of treason or rebellion against the Empire, and when Leia lies about the location of the Rebel base. (Even the latter isn’t an act of amorality, when facing the pure evilness of the Death Star.)

The Rebellion we see in Rogue One, however, is very different. Even ignoring the extremism of Saw Gerrara, who was no longer part of the Rebellion, the movie opens with Andor shockingly killing his informant on the space station in the Rings of Kafrene. While his action may be justified by mercy and by the need for operational security, Andor’s murder of the informant stands in stark contrast to the actions of the Jedi in the Prequel Trilogy or Luke in the OT.

In one emotion scene in Rogue One, Andor tells Jyn that many of the Rebels “have done terrible things on behalf of the Rebellion. We’re spies. Saboteurs. Assasins. And every time I wanted to forget I told myself it was for a cause that I believed in. A cause that was worth it.”

And why did Andor confess this to Jyn? The Rebellion had been using Jyn to find Galen Erso, using her to find her father to kill him, as General Draven quietly ordered Andor: “You find him, you kill him.”

So essentially, the Rebellion we see in Rogue One is a rebellion focused on fighting the evil of the Empire, but one that is not necessarily fighting for good. They are not driven by morality, by their desire to spread good throughout the galaxy, but by opposition to immorality.

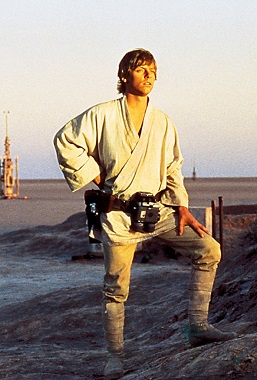

Enter Luke Skywalker.

Young Luke is driven by wanderlust and a desire for adventure, essentially imprisoned (as was Anakin) on Tatooine, a place where his natural talents for flying and his spirit of the Force cannot be realized.

But he is also driven by a moral concern for other people, an innate sense of goodness. From his first glimpse of hologram-Leia, he sees someone in need and wants to help her. When he resists leaving Tatooine, Ben Kenobi can sense that that’s not Luke’s real feelings: “That’s your uncle talking,” he chides Luke. Ben knows the real Luke.

After that, at every opportunity, Luke takes the selfless path: he chooses to go save Leia, someone he does not know, at great risk to himself; then, at the end, he chooses to stay with the Rebellion on Yavin IV and fight, even though he had just joined the group, had no loyalty to them, and could have easily left with Han. Han serves as the perfect foil for these two decisions Luke makes: Luke has to convince Han to go save Leia by promising money and rewards, and Luke shows real disappointment in Han when Han leaves Yavin IV ahead of the Battle of Yavin (“You know what’s about to happen, what they’re up against.” “Take care of yourself—I guess that’s what you’re best at, isn’t it?”

Luke is driven by an inner morality, by selfless care and concern for others. The Rebellion that we see in Rogue One isn’t.

Luke’s devotion to what we later learn is the Light Side continues in the Empire Strikes Back when Luke foregoes his continued Jedi training to save his friends, and then in Return of the Jedi when Luke, alone, goes to face Darth Vader. “There is still good in him,” Luke insists. But Luke also knows that, if he is wrong, his confronting of Darth Vader is still a worthy sacrifice, because his presence with the Endor team endangers them. He is willing to make that sacrifice to save his friends, to save the Rebellion, and to save the Galaxy.

Luke is a beacon of light, a redemptive figure who is driven by a selfless belief in helping others. While he does hate the Empire, when faced with choices during the OT, he always chooses to take the path that can help others and spread goodness, even at great risk to himself. (Oh, let’s not contrast this with the Luke of Episode VIII. We just won’t go there.)

The Rebellion, just before the Battles of Scarif and Endor, is full of spies, saboteurs, and assassins—people whose sole driving principle is the destruction of the Empire. Enter Luke Skywalker—not only does he save the Rebellion at the Battle of Yavin, he saves the very soul of the Rebellion.